Jackson, Mississippi on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Jackson, officially the City of Jackson, is the

Located on the historic

Located on the historic

Despite its small population, during the Civil War, Jackson became a strategic center of manufacturing for the Confederacy. In 1863, during the military campaign which ended in the capture of Vicksburg,

Despite its small population, during the Civil War, Jackson became a strategic center of manufacturing for the Confederacy. In 1863, during the military campaign which ended in the capture of Vicksburg,  Because of the siege and following destruction, few

Because of the siege and following destruction, few

Author

Author

The mass demonstrations of the 1960s were initiated with the arrival of more than 300

The mass demonstrations of the 1960s were initiated with the arrival of more than 300

, Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life website, History Department, Digital Archive, Mississippi, Jackson, Beth Israel. Retrieved August 17, 2008. He and his congregation had supported civil rights. Gradually the old barriers came down. Since that period, both whites and African Americans in the state have had a consistently high rate of voter registration and turnout. Following the decades of the Great Migration, when more than one million black people left the rural South, since the 1930s the state has been majority white in total population. African Americans are a majority in the city of Jackson, although the metropolitan area is majority white. African Americans are also a majority in several cities and counties of the

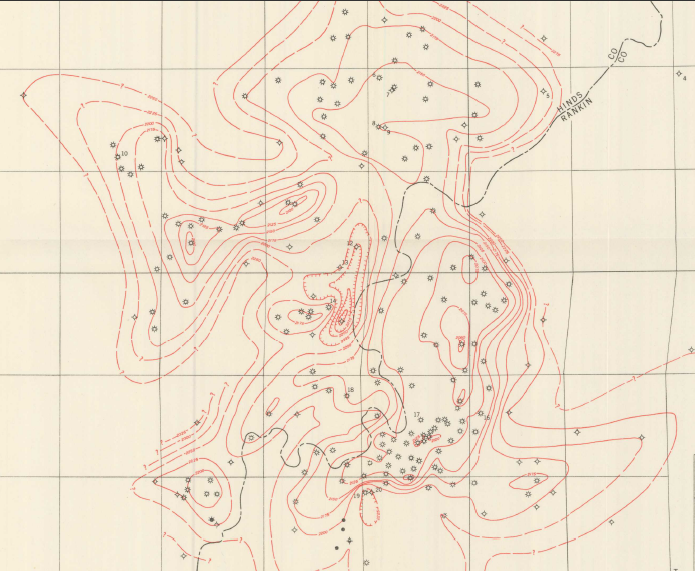

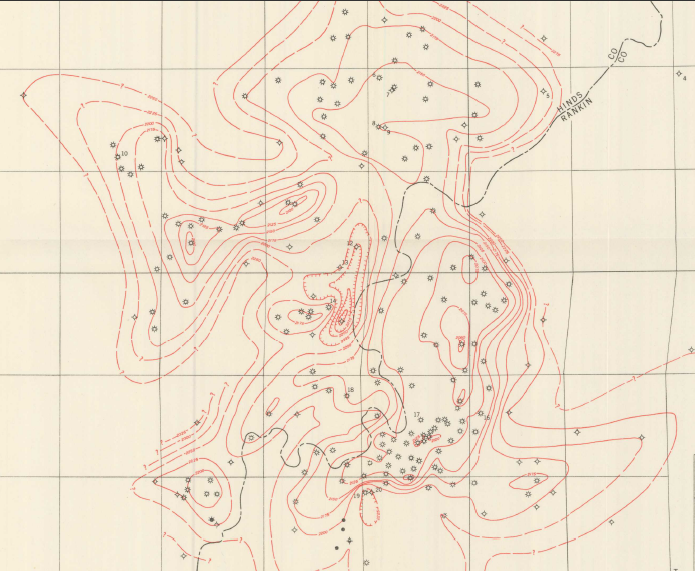

Jackson is located primarily in northeastern Hinds County, with small portions in

Jackson is located primarily in northeastern Hinds County, with small portions in

Downtown Jackson is situated directly on the banks of the Pearl River. The downtown district has direct connections to both Interstate 55 via Pearl Street and Pasagoula Street and Interstate 20 via State Street (US 51). Much of the downtown was constructed before the 1980s and only small additions to the skyline have been made since then.

Downtown Jackson is situated directly on the banks of the Pearl River. The downtown district has direct connections to both Interstate 55 via Pearl Street and Pasagoula Street and Interstate 20 via State Street (US 51). Much of the downtown was constructed before the 1980s and only small additions to the skyline have been made since then.

Interstate 220

*

Interstate 220

*

Jackson sits atop the extinct

Jackson sits atop the extinct

According to the 2010 census, the racial and ethnic makeup of the city was predominantly Black and African American, and

According to the 2010 census, the racial and ethnic makeup of the city was predominantly Black and African American, and

Jackson is home to a number of cultural and artistic attractions, including the following:

* Ballet Mississippi

* Celtic Heritage Society of Mississippi

* Crossroads Film Society and its annual Film Festival

* International Museum of Muslim Cultures

* Jackson State University Botanical Garden

* Jackson Zoo

*

Jackson is home to a number of cultural and artistic attractions, including the following:

* Ballet Mississippi

* Celtic Heritage Society of Mississippi

* Crossroads Film Society and its annual Film Festival

* International Museum of Muslim Cultures

* Jackson State University Botanical Garden

* Jackson Zoo

*

The city of Jackson and its metropolitan area are home to collegiate and semi-professional sports teams;

The city of Jackson and its metropolitan area are home to collegiate and semi-professional sports teams;

Jackson is home to the most collegiate institutions in Mississippi.

Jackson is home to the most collegiate institutions in Mississippi.

, Jackson Convention and Visitors Bureau In the song "

Jackson Convention & Visitors BureauMetro Jackson Chamber of Commerce

{{Authority control Cities in Mississippi Cities in Hinds County, Mississippi Cities in Madison County, Mississippi Cities in Rankin County, Mississippi 1792 establishments in the United States Andrew Jackson County seats in Mississippi Cities in Jackson metropolitan area, Mississippi Mississippi Blues Trail Planned cities in the United States Populated places established in 1792

capital

Capital may refer to:

Common uses

* Capital city, a municipality of primary status

** List of national capital cities

* Capital letter, an upper-case letter Economics and social sciences

* Capital (economics), the durable produced goods used f ...

of and the most populous city in the U.S. state

In the United States, a state is a constituent political entity, of which there are 50. Bound together in a political union, each state holds governmental jurisdiction over a separate and defined geographic territory where it shares its sover ...

of Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

. The city is also one of two county seats of Hinds County

Hinds County is a county located in the U.S. state of Mississippi. With its county seats ( Raymond and the state's capital, Jackson), Hinds is the most populous county in Mississippi with a 2020 census population of 227,742 residents. Hinds Cou ...

, along with Raymond

Raymond is a male given name. It was borrowed into English from French (older French spellings were Reimund and Raimund, whereas the modern English and French spellings are identical). It originated as the Germanic ᚱᚨᚷᛁᚾᛗᚢᚾᛞ ( ...

. The city had a population of 153,701 at the 2020 census, down from 173,514 at the 2010 census. Jackson's population declined more between 2010 and 2020 (11.42%) than any major city

The United Nations uses three definitions for what constitutes a city, as not all cities in all jurisdictions are classified using the same criteria. Cities may be defined as the cities proper, the extent of their urban area, or their metropo ...

in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

. Jackson is the anchor for the Jackson metropolitan statistical area, the largest metropolitan area

A metropolitan area or metro is a region that consists of a densely populated urban agglomeration and its surrounding territories sharing industries, commercial areas, transport network, infrastructures and housing. A metro area usually com ...

completely within the state. With a 2020 population estimated around 600,000, metropolitan Jackson is home to over one-fifth of Mississippi's population. The city sits on the Pearl River

The Pearl River, also known by its Chinese name Zhujiang or Zhu Jiang in Mandarin pinyin or Chu Kiang and formerly often known as the , is an extensive river system in southern China. The name "Pearl River" is also often used as a catch-a ...

and is located in the greater Jackson Prairie

The Jackson Prairie is a temperate grassland ecoregion in Mississippi. It is a disjunct of the Black Belt (or Black Prairie) physiographic area.

Description

The prairie is a narrow strip across the state from the Mississippi River to the bo ...

region of Mississippi.

Founded in 1821 as the site for a new state capital, the city is named after General Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

, who was honored for his role in the Battle of New Orleans

The Battle of New Orleans was fought on January 8, 1815 between the British Army under Major General Sir Edward Pakenham and the United States Army under Brevet Major General Andrew Jackson, roughly 5 miles (8 km) southeast of the French ...

during the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It bega ...

and would later serve as U.S. president. Following the nearby Battle of Vicksburg

The siege of Vicksburg (May 18 – July 4, 1863) was the final major military action in the Vicksburg campaign of the American Civil War. In a series of maneuvers, Union Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and his Army of the Tennessee crossed the Missis ...

in 1863 during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, Union forces under the command of General William Tecumseh Sherman

William Tecumseh Sherman ( ; February 8, 1820February 14, 1891) was an American soldier, businessman, educator, and author. He served as a general in the Union Army during the American Civil War (1861–1865), achieving recognition for his com ...

began the siege of Jackson

The Jackson Expedition, also known as the Siege of Jackson, occurred in the aftermath of the surrender of Vicksburg, Mississippi, in July 1863. Union Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman led the expedition to clear General Joseph E. Johnston ...

and the city was subsequently burned.

During the 1920s, Jackson surpassed Meridian

Meridian or a meridian line (from Latin ''meridies'' via Old French ''meridiane'', meaning “midday”) may refer to

Science

* Meridian (astronomy), imaginary circle in a plane perpendicular to the planes of the celestial equator and horizon

* ...

to become the most populous city in the state following a speculative natural gas

Natural gas (also called fossil gas or simply gas) is a naturally occurring mixture of gaseous hydrocarbons consisting primarily of methane in addition to various smaller amounts of other higher alkanes. Low levels of trace gases like carbo ...

boom in the region. The current slogan for the city is "The City with Soul". It has had numerous musicians prominent in blues

Blues is a music genre and musical form which originated in the Deep South of the United States around the 1860s. Blues incorporated spirituals, work songs, field hollers, shouts, chants, and rhymed simple narrative ballads from the Afr ...

, gospel

Gospel originally meant the Christian message ("the gospel"), but in the 2nd century it came to be used also for the books in which the message was set out. In this sense a gospel can be defined as a loose-knit, episodic narrative of the words an ...

, folk

Folk or Folks may refer to:

Sociology

*Nation

*People

* Folklore

** Folk art

** Folk dance

** Folk hero

** Folk music

*** Folk metal

*** Folk punk

*** Folk rock

** Folk religion

* Folk taxonomy

Arts, entertainment, and media

* Folk Plus or Fol ...

, and jazz

Jazz is a music genre that originated in the African-American communities of New Orleans, Louisiana in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with its roots in blues and ragtime. Since the 1920s Jazz Age, it has been recognized as a major ...

. The city is located in the deep south

The Deep South or the Lower South is a cultural and geographic subregion in the Southern United States. The term was first used to describe the states most dependent on plantations and slavery prior to the American Civil War. Following the war ...

halfway between Memphis

Memphis most commonly refers to:

* Memphis, Egypt, a former capital of ancient Egypt

* Memphis, Tennessee, a major American city

Memphis may also refer to:

Places United States

* Memphis, Alabama

* Memphis, Florida

* Memphis, Indiana

* Memp ...

and New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

on Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

Interstate 55

Interstate 55 (I-55) is a major Interstate Highway in the central United States. As with most primary Interstates that end in a five, it is a major cross-country, north–south route, connecting the Gulf of Mexico to the Great Lakes. The h ...

and Shreveport

Shreveport ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Louisiana. It is the third most populous city in Louisiana after New Orleans and Baton Rouge, Louisiana, Baton Rouge, respectively. The Shreveport–Bossier City metropolitan area, with a population o ...

, Louisiana and Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1.145 million in the city proper, 2.92 million in the West ...

, Alabama on Interstate 20

Interstate 20 (I‑20) is a major east–west Interstate Highway in the Southern United States. I-20 runs beginning at an interchange with Interstate 10, I-10 in Scroggins Draw, Texas, and ending at an interchange with Interstate 95, I-95 in Flo ...

. Being at this location has given the city the nickname the "crossroads of the south".

The city has a number of museums and cultural institutions, including the Mississippi Childrens Museum, Mississippi Museum of Natural Science, Mississippi Civil Rights Museum

The Mississippi Civil Rights Museum is a museum in Jackson, Mississippi. Its mission is to document, exhibit the history of, and educate the public about the American Civil Rights Movement in the U.S. state of Mississippi between 1945 and 1970.

, Mississippi Museum of Art

The Mississippi Museum of Art is a public museum in Jackson, Mississippi. It is the largest museum in Mississippi.

Location

It is located at the corner of 380 South Lamar Street and 201 East Pascagoula Street in Jackson, Mississippi.Lee Ellis, ''F ...

, Old Capital Museum, Museum of Mississippi History

The Museum of Mississippi History is a museum in Jackson, Mississippi. The museum opened December 9, 2017, in conjunction with the adjacent Mississippi Civil Rights Museum in celebration of Mississippi's bicentennial. The theme of the history mus ...

. Other notable locations are the Mississippi Coliseum and the Mississippi Veterans Memorial Stadium, home of the Jackson State Tigers Football

The Jackson State Tigers football team represents Jackson State University in college football at the NCAA Division I Football Championship Subdivision (FCS) level as a member of the Southwestern Athletic Conference (SWAC).

After joining the So ...

Team.

The Jackson metropolitan statistical area is the state's second largest metropolitan area overall, due to four counties in northern Mississippi being part of the Memphis, Tennessee metropolitan area. In 2020, the Jackson metropolitan area held a GDP

Gross domestic product (GDP) is a monetary measure of the market value of all the final goods and services produced and sold (not resold) in a specific time period by countries. Due to its complex and subjective nature this measure is ofte ...

of 30 billion dollars, accounting for 29% of the state's total GDP of 104.1 billion dollars.

History

Native Americans

The region that is now the city of Jackson was historically part of the large territory occupied by theChoctaw

The Choctaw (in the Choctaw language, Chahta) are a Native American people originally based in the Southeastern Woodlands, in what is now Alabama and Mississippi. Their Choctaw language is a Western Muskogean language. Today, Choctaw people are ...

Nation. The Choctaw name for the locale was ''Chisha Foka''. The area now called Jackson was obtained by the United States under the terms of the Treaty of Doak's Stand

The Treaty of Doak's Stand (7 Stat. 210, also known as Treaty with the Choctaw) was signed on October 18, 1820 (proclaimed on January 8, 1821) between the United States and the Choctaw Indian tribe. Based on the terms of the accord, the Choctaw ...

in 1820, by which the United States acquired the land owned by the Choctaw Native Americans. After the treaty was ratified, American settlers moved into the area, encroaching on remaining Choctaw communal lands. One of the original Choctaw members, in 1849, described what he and his people experienced during this turbulent time when the Europeans had come to take their land. "We have had our habitations torn down and burned" as well as their "fences burned" while they constantly faced personal abuse and have been "scoured, manacled and fettered".

Under pressure from the U.S. government, the Choctaw Native Americans agreed to removal after 1830 from all of their lands east of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

under the terms of several treaties

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between actors in international law. It is usually made by and between sovereign states, but can include international organizations, individuals, business entities, and other legal perso ...

. Although most of the Choctaw moved to Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the Federal government of the United States, United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans in the United St ...

in present-day Oklahoma

Oklahoma (; Choctaw language, Choctaw: ; chr, ᎣᎧᎳᎰᎹ, ''Okalahoma'' ) is a U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States, bordered by Texas on the south and west, Kansas on the nor ...

, along with the other of the Five Civilized Tribes

The term Five Civilized Tribes was applied by European Americans in the colonial and early federal period in the history of the United States to the five major Native American nations in the Southeast—the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek ...

, a significant number chose to stay in their homeland, citing Article XIV of the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek

The Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek was a treaty which was signed on September 27, 1830, and proclaimed on February 24, 1831, between the Choctaw American Indian tribe and the United States Government. This treaty was the first removal treaty wh ...

. They gave up their tribal membership and became state and United States citizens at the time. Today, most Choctaw in Mississippi have reorganized and are part of the federally recognized Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians

The Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians ( cho, Mississippi Chahta) is one of three federally recognized tribes of Choctaw Native Americans, and the only one in the state of Mississippi. On April 20, 1945, this tribe organized under the Indian R ...

. They live in several majority- Indian communities located throughout the state. The largest community is located in Choctaw

The Choctaw (in the Choctaw language, Chahta) are a Native American people originally based in the Southeastern Woodlands, in what is now Alabama and Mississippi. Their Choctaw language is a Western Muskogean language. Today, Choctaw people are ...

northeast of Jackson.

Founding and antebellum period (to 1860)

Located on the historic

Located on the historic Natchez Trace

The Natchez Trace, also known as the Old Natchez Trace, is a historic forest trail within the United States which extends roughly from Nashville, Tennessee, to Natchez, Mississippi, linking the Cumberland, Tennessee, and Mississippi rivers. ...

trade route, created by Native Americans and used by European American settlers, and on the Pearl River, the city's first European American settler was Louis LeFleur, a French-Canadian

French Canadians (referred to as Canadiens mainly before the twentieth century; french: Canadiens français, ; feminine form: , ), or Franco-Canadians (french: Franco-Canadiens), refers to either an ethnic group who trace their ancestry to Fr ...

trader. The village became known as LeFleur's Bluff

LeFleur's Bluff State Park is a public recreation area located on the banks of the Pearl River (Mississippi–Louisiana), Pearl River off Interstate 55 within the city limits of Jackson, Mississippi, Jackson, Mississippi. The state park is home ...

. During the late 18th century and early 19th century, this site had a trading post

A trading post, trading station, or trading house, also known as a factory, is an establishment or settlement where goods and services could be traded.

Typically the location of the trading post would allow people from one geographic area to tr ...

. It was connected to markets in Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked state in the Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the 36th-largest by area and the 15th-most populous of the 50 states. It is bordered by Kentucky to th ...

. Soldiers returning to Tennessee from the military campaigns near New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

in 1815 built a public road that connected Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

Lake Pontchartrain

Lake Pontchartrain ( ) is an estuary located in southeastern Louisiana in the United States. It covers an area of with an average depth of . Some shipping channels are kept deeper through dredging. It is roughly oval in shape, about from west ...

in Louisiana to this district. A United States treaty with the Choctaw, the Treaty of Doak's Stand

The Treaty of Doak's Stand (7 Stat. 210, also known as Treaty with the Choctaw) was signed on October 18, 1820 (proclaimed on January 8, 1821) between the United States and the Choctaw Indian tribe. Based on the terms of the accord, the Choctaw ...

in 1820, formally opened the area for non-Native American settlers.

LeFleur's Bluff was developed when it was chosen as the site for the new state's capital city

A capital city or capital is the municipality holding primary status in a country, state, province, Department (country subdivision), department, or other subnational entity, usually as its seat of the government. A capital is typically a city ...

. The Mississippi General Assembly decided in 1821 that the state needed a centrally located capital (the legislature was then located in Natchez Natchez may refer to:

Places

* Natchez, Alabama, United States

* Natchez, Indiana, United States

* Natchez, Louisiana, United States

* Natchez, Mississippi, a city in southwestern Mississippi, United States

* Grand Village of the Natchez, a site o ...

). They commissioned Thomas Hinds

Thomas Hinds (January 9, 1780August 23, 1840) was an American soldier and politician from the state of Mississippi, who served in the United States Congress from 1828 to 1831.

A hero of the War of 1812, Hinds is best known today as the namesake ...

, James Patton, and William Lattimore to look for a suitable site. The absolute center of the state was a swamp, so the group had to widen their search.

After surveying areas north and east of Jackson, they proceeded southwest along with the Pearl River

The Pearl River, also known by its Chinese name Zhujiang or Zhu Jiang in Mandarin pinyin or Chu Kiang and formerly often known as the , is an extensive river system in southern China. The name "Pearl River" is also often used as a catch-a ...

until they reached LeFleur's Bluff in today's Hinds County. Their report to the General Assembly stated that this location had beautiful and healthful surroundings, good water, abundant timber, navigable waters, and proximity to the Natchez Trace

The Natchez Trace, also known as the Old Natchez Trace, is a historic forest trail within the United States which extends roughly from Nashville, Tennessee, to Natchez, Mississippi, linking the Cumberland, Tennessee, and Mississippi rivers. ...

. The Assembly passed an act on November 28, 1821, authorizing the site as the permanent seat of the government of the state of Mississippi. On the same day, it passed a resolution to instruct the Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

delegation to press Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of a ...

for a donation of public lands on the river for improved navigation to the Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico ( es, Golfo de México) is an oceanic basin, ocean basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, largely surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north and northwest by the Gulf Coast of ...

. One Whig politician lamented the new capital as a "serious violation of principle" because it was not at the absolute center of the state.

The capital was named for General Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

, to honor his (January 1815) victory at the Battle of New Orleans

The Battle of New Orleans was fought on January 8, 1815 between the British Army under Major General Sir Edward Pakenham and the United States Army under Brevet Major General Andrew Jackson, roughly 5 miles (8 km) southeast of the French ...

during the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It bega ...

. He was later elected as the seventh president of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United Stat ...

.

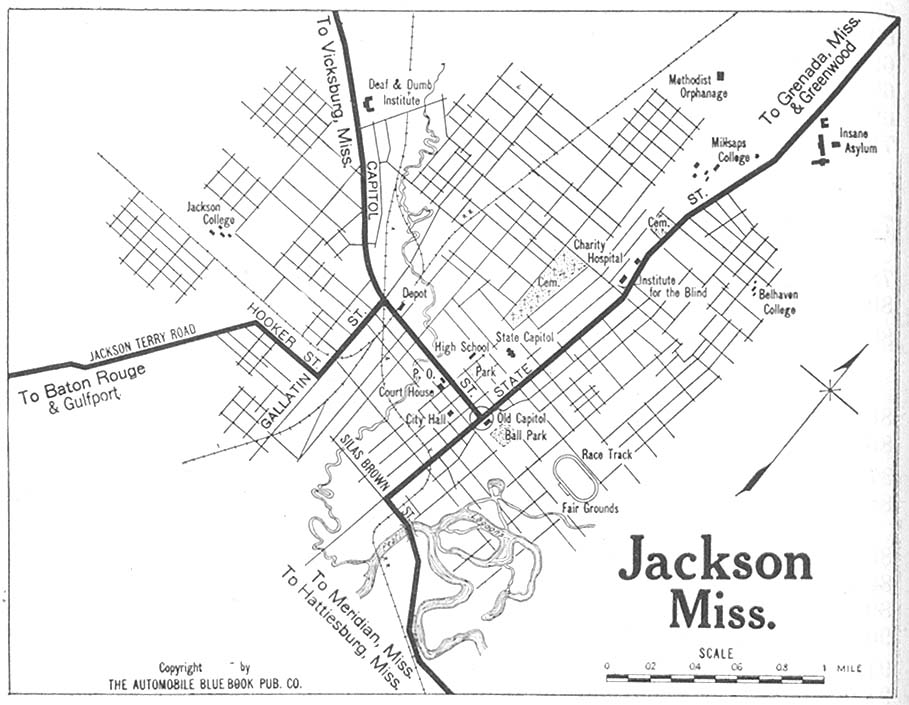

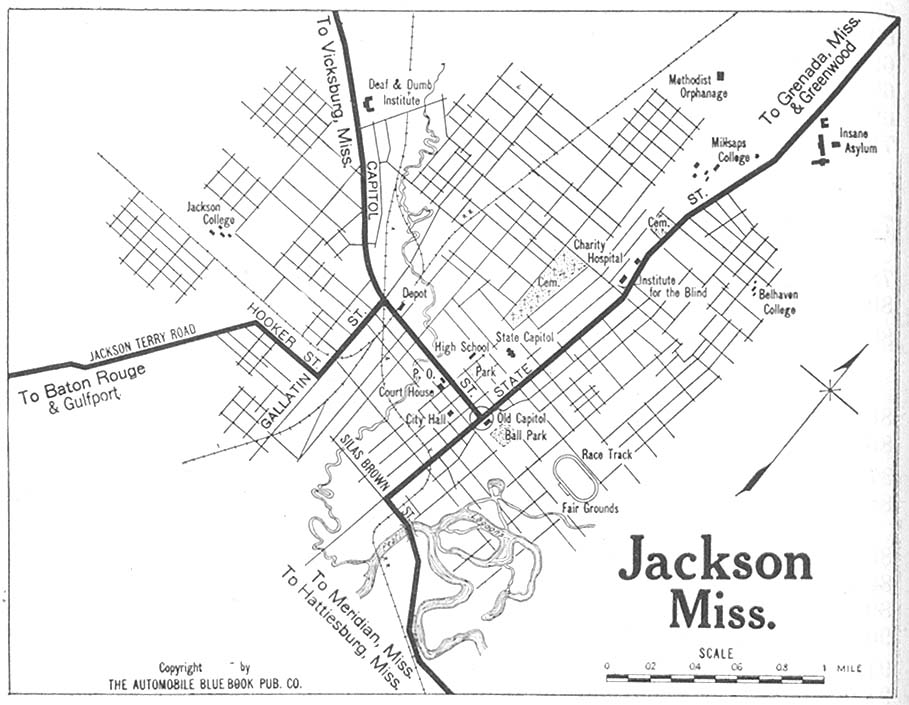

The city of Jackson was originally planned, in April 1822, by Peter Aaron Van Dorn in a "checkerboard

A checkerboard (American English) or chequerboard (British English; see spelling differences) is a board of checkered pattern on which checkers (also known as English draughts) is played. Most commonly, it consists of 64 squares (8×8) of altern ...

" pattern advocated by Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

. City block

A city block, residential block, urban block, or simply block is a central element of urban planning and urban design.

A city block is the smallest group of buildings that is surrounded by streets, not counting any type of thoroughfare within t ...

s alternated with parks and other open spaces. Over time, many of the park squares have been developed rather than maintained as green space. The state legislature first met in Jackson on December 23, 1822. In 1839, the Mississippi Legislature passed the first state law in the U.S. to permit married women to own and administer their own property.

Jackson was connected by public road to Vicksburg Vicksburg most commonly refers to:

* Vicksburg, Mississippi, a city in western Mississippi, United States

* The Vicksburg Campaign, an American Civil War campaign

* The Siege of Vicksburg, an American Civil War battle

Vicksburg is also the name of ...

and Clinton in 1826. Jackson was first connected by railroad to other cities in 1840. An 1844 map shows Jackson linked by an east–west rail line running between Vicksburg, Raymond

Raymond is a male given name. It was borrowed into English from French (older French spellings were Reimund and Raimund, whereas the modern English and French spellings are identical). It originated as the Germanic ᚱᚨᚷᛁᚾᛗᚢᚾᛞ ( ...

, and Brandon

Brandon may refer to:

Names and people

*Brandon (given name), a male given name

*Brandon (surname), a surname with several different origins

Places

Australia

*Brandon, a farm and 19th century homestead in Seaham, New South Wales

*Brandon, Q ...

. Unlike Vicksburg, Greenville, and Natchez Natchez may refer to:

Places

* Natchez, Alabama, United States

* Natchez, Indiana, United States

* Natchez, Louisiana, United States

* Natchez, Mississippi, a city in southwestern Mississippi, United States

* Grand Village of the Natchez, a site o ...

, Jackson is not located on the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

, and it did not develop during the antebellum era

In the history of the Southern United States, the Antebellum Period (from la, ante bellum, lit= before the war) spanned the end of the War of 1812 to the start of the American Civil War in 1861. The Antebellum South was characterized by the ...

as those cities did from major river commerce. The construction of railroad lines to the city sparked its growth in the decades following the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

.

American Civil War

Despite its small population, during the Civil War, Jackson became a strategic center of manufacturing for the Confederacy. In 1863, during the military campaign which ended in the capture of Vicksburg,

Despite its small population, during the Civil War, Jackson became a strategic center of manufacturing for the Confederacy. In 1863, during the military campaign which ended in the capture of Vicksburg, Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

forces captured Jackson during two battles—once before the fall of Vicksburg and once after the fall of Vicksburg.

On May 13, 1863, Union forces won the first Battle of Jackson, forcing Confederate

Confederacy or confederate may refer to:

States or communities

* Confederate state or confederation, a union of sovereign groups or communities

* Confederate States of America, a confederation of secessionist American states that existed between 1 ...

forces to flee northward towards Canton. On May 14, Union troops under the command of William Tecumseh Sherman

William Tecumseh Sherman ( ; February 8, 1820February 14, 1891) was an American soldier, businessman, educator, and author. He served as a general in the Union Army during the American Civil War (1861–1865), achieving recognition for his com ...

burned and looted key facilities in Jackson, a strategic manufacturing and railroad center for the Confederacy. After driving the Confederate forces out of Jackson, Union forces turned west and engaged the Vicksburg defenders at the Battle of Champion Hill

The Battle of Champion Hill of May 16, 1863, was the pivotal battle in the Vicksburg Campaign of the American Civil War (1861–1865). Union Army commander Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and the Army of the Tennessee pursued the retreating Confe ...

in nearby Edwards Edwards may refer to:

People

* Edwards (surname)

* Edwards family, a prominent family from Chile

* Edwards Barham (1937-2014), a former member of the Louisiana State Senate

* Edwards Pierrepont (1817–1892), an American attorney, jurist, and ora ...

. The Union forces began their siege of Vicksburg soon after their victory at Champion Hill. Confederate forces began to reassemble in Jackson in preparation for an attempt to break through the Union lines surrounding Vicksburg and end the siege. The Confederate forces in Jackson built defensive fortification

A fortification is a military construction or building designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is also used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin ''fortis'' ("strong") and ''facere'' ...

s encircling the city while preparing to march west to Vicksburg.

Confederate forces marched out of Jackson in early July 1863 to break the siege of Vicksburg. But, unknown to them, Vicksburg had already surrendered on July 4, 1863. General Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

dispatched General Sherman to meet the Confederate forces heading west from Jackson. Upon learning that Vicksburg had already surrendered, the Confederates retreated into Jackson. Union forces began the siege of Jackson

The Jackson Expedition, also known as the Siege of Jackson, occurred in the aftermath of the surrender of Vicksburg, Mississippi, in July 1863. Union Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman led the expedition to clear General Joseph E. Johnston ...

, which lasted for approximately one week. Union forces encircled the city and began an artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during siege ...

bombardment. One of the Union artillery emplacements has been preserved on the grounds of the University of Mississippi Medical Center

University of Mississippi Medical Center (UMMC) is the health sciences campus of the University of Mississippi (Ole Miss) and is located in Jackson, Mississippi, United States. UMMC, also referred to as the Medical Center, is the state's only aca ...

in Jackson. Another Federal position is preserved on the campus of Millsaps College

Millsaps College is a private liberal arts college in Jackson, Mississippi. It was founded in 1890 and is affiliated with the United Methodist Church.

History

The college was founded in 1889–90 by a Confederate veteran, Major Reuben Webster M ...

. John C. Breckinridge

John Cabell Breckinridge (January 16, 1821 – May 17, 1875) was an American lawyer, politician, and soldier. He represented Kentucky in both houses of Congress and became the 14th and youngest-ever vice president of the United States. Serving ...

, former United States vice president

A vice president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vice president is on t ...

, served as one of the Confederate generals defending Jackson. On July 16, 1863, Confederate forces slipped out of Jackson during the night and retreated across the Pearl River.

Union forces completely burned the city after its capture this second time. The city was called "Chimneyville" because only the chimneys of houses were left standing. The northern line of Confederate defenses in Jackson during the siege was located along a road near downtown Jackson, now known as Fortification Street.

Because of the siege and following destruction, few

Because of the siege and following destruction, few antebellum

Antebellum, Latin for "before war", may refer to:

United States history

* Antebellum South, the pre-American Civil War period in the Southern United States

** Antebellum Georgia

** Antebellum South Carolina

** Antebellum Virginia

* Antebellum ...

structures have survived in Jackson. The Governor's Mansion, built-in 1842, served as Sherman's headquarters and has been preserved. Another is the Old Capitol building, which served as the home of the Mississippi state legislature from 1839 to 1903. The Mississippi legislature passed the ordinance of secession

Secession is the withdrawal of a group from a larger entity, especially a political entity, but also from any organization, union or military alliance. Some of the most famous and significant secessions have been: the former Soviet republics le ...

from the Union on January 9, 1861, there, becoming the second state to secede from the United States. The Jackson City Hall, built in 1846 for less than $8,000, also survived. It is said that Sherman, a Mason, spared it because it housed a Masonic Lodge

A Masonic lodge, often termed a private lodge or constituent lodge, is the basic organisational unit of Freemasonry. It is also commonly used as a term for a building in which such a unit meets. Every new lodge must be warranted or chartered ...

, though a more likely reason is that it housed an army hospital.

Reconstruction

DuringReconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*'' Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

, Republicans granted African Americans civil rights. Schools were established and African Americans held political offices. Eugene Welborne, Charles Reese, Weldon Hicks, and George Caldwell Granberry were among the legislators who represented Hinds County in the legislature. African Americans also served in local offices, as judges, and as marshalls.

Mississippi had considerable insurgent action, as whites struggled to maintain white supremacy. Jackson’s appointed mayor Joseph G. Crane

Joseph G. Crane was a Union Army officer who was appointed mayor of Jackson, Mississippi (the state capitol) in 1869. He was stabbed to death on the capitol steps by Edward M. Yerger, a former Confederate Army officer who edited a newspaper. After ...

was stabbed to death in 1869. The assailant, Edward M. Yerger

Edward M. Yerger (1828 – April 22, 1875) was an American newspaper editor and military officer. After a career in the newspaper industry, Yerger was arrested for the stabbing death of the provisional mayor of Jackson, Mississippi. His claim of ...

, was arrested by military authorities but, after a U.S. Supreme Court case (Ex parte Yerger

''Ex parte Yerger'', 75 U.S. (8 Wall.) 85 (1869), was a case heard by the Supreme Court of the United States in which the court held that, under the Judiciary Act of 1789, it is authorized to issue writs of habeas corpus.

Background

In June 1869 ...

), he was bonded out, moved to Baltimore and was never tried.

The economic recovery from the Civil War was slow through the start of the 20th century, but there were some developments in transportation. In 1871, the city introduced mule-drawn streetcars which ran on State Street, which were replaced by electric ones in 1899. In 1875, the Red Shirts were formed, one of the second waves of insurgent paramilitary

A paramilitary is an organization whose structure, tactics, training, subculture, and (often) function are similar to those of a professional military, but is not part of a country's official or legitimate armed forces. Paramilitary units carr ...

organizations that essentially operated as "the military arm of the Democratic Party" to take back political power from the Republicans and to drive black people from the polls (Mississippi Plan

The Mississippi Plan of 1875 was developed by white Southern Democrats as part of the white insurgency during the Reconstruction Era in the Southern United States. It was devised by the Democratic Party in that state to overthrow the Republican Pa ...

).

Post-Reconstruction

Democrats regained control of the state legislature in 1876. The constitutional convention of 1890, which produced Mississippi's Constitution of 1890, was held at the capitol. This was the first of new constitutions or amendments ratified in each Southern state through 1908 that effectivelydisenfranchised

Disfranchisement, also called disenfranchisement, or voter disqualification is the restriction of suffrage (the right to vote) of a person or group of people, or a practice that has the effect of preventing a person exercising the right to vote. D ...

most African Americans

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

and many poor whites, through provisions making voter registration more difficult: such as poll taxes

A poll tax, also known as head tax or capitation, is a tax levied as a fixed sum on every liable individual (typically every adult), without reference to income or resources.

Head taxes were important sources of revenue for many governments fr ...

, residency requirements, and literacy test

A literacy test assesses a person's literacy skills: their ability to read and write have been administered by various governments, particularly to immigrants. In the United States, between the 1850s and 1960s, literacy tests were administered t ...

s. These provisions survived a Supreme Court challenge in 1898. As 20th-century Supreme Court decisions later ruled such provisions were unconstitutional, Mississippi and other Southern states rapidly devised new methods to continue disfranchisement of most black people, who comprised a majority in the state until the 1930s. Their exclusion from politics was maintained into the late 1960s.

The so-called New Capitol replaced the older structure upon its completion in 1903. Today the Old Capitol is operated as a historical museum.

Early 20th century (1901–1960)

Author

Author Eudora Welty

Eudora Alice Welty (April 13, 1909 – July 23, 2001) was an American short story writer, novelist and photographer who wrote about the American South. Her novel ''The Optimist's Daughter'' won the Pulitzer Prize in 1973. Welty received numero ...

was born in Jackson in 1909, lived most of her life in the Belhaven section of the city, and died there in 2001. Her memoir

A memoir (; , ) is any nonfiction narrative writing based in the author's personal memories. The assertions made in the work are thus understood to be factual. While memoir has historically been defined as a subcategory of biography or autobi ...

of development as a writer, '' One Writer's Beginnings'' (1984), presented a picture of the city in the early 20th century. She won the Pulitzer Prize

The Pulitzer Prize () is an award for achievements in newspaper, magazine, online journalism, literature, and musical composition within the United States. It was established in 1917 by provisions in the will of Joseph Pulitzer, who had made h ...

in 1973 for her novel, ''The Optimist's Daughter

''The Optimist's Daughter'' is a Pulitzer Prize for Fiction-winning short novel by Eudora Welty. It was first published as a long story in ''The New Yorker'' in March 1969 and was subsequently revised and published in book form in 1972. It conce ...

,'' and is best known for her novels and short stories. The main library of the Jackson/Hinds Library System

Jackson/Hinds Library System (JHLS) is the public library system of Jackson and Hinds County in Mississippi.

Branches

; Jackson

* Eudora Welty Library - It is the main library and is in a former Sears building, built circa 1938. As of 2018 the se ...

was named in her honor, and her home has been designated as a National Historic Landmark

A National Historic Landmark (NHL) is a building, district, object, site, or structure that is officially recognized by the United States government for its outstanding historical significance. Only some 2,500 (~3%) of over 90,000 places listed ...

.

Richard Wright, a highly acclaimed African-American author, lived in Jackson as an adolescent and young man in the 1910s and 1920s. He related his experience in his memoir ''Black Boy

''Black Boy'' (1945) is a memoir by American author Richard Wright, detailing his upbringing. Wright describes his youth in the South: Mississippi, Arkansas and Tennessee, and his eventual move to Chicago, where he establishes his writing care ...

'' (1945). He described the harsh and largely terror-filled life most African Americans experienced in the South and Northern ghettos such as Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

under segregation Segregation may refer to:

Separation of people

* Geographical segregation, rates of two or more populations which are not homogenous throughout a defined space

* School segregation

* Housing segregation

* Racial segregation, separation of humans ...

in the early 20th century. Jackson had significant growth in the early 20th century, which produced dramatic changes in the city's skyline. Jackson's new Union Station

A union station (also known as a union terminal, a joint station in Europe, and a joint-use station in Japan) is a railway station at which the tracks and facilities are shared by two or more separate railway companies, allowing passengers to ...

downtown reflected the city's service by multiple rail lines, including the Illinois Central.

Across the street, the new, luxurious King Edward Hotel opened its doors in 1923, having been built according to a design by New Orleans architect William T. Nolan. It became a center for prestigious events held by Jackson society and Mississippi politicians. Nearby, the 18-story Standard Life Building, designed in 1929 by Claude Lindsley, was the largest reinforced concrete structure in the world upon its completion.

Jackson's economic growth was further stimulated in the 1930s by the discovery of natural gas

Natural gas (also called fossil gas or simply gas) is a naturally occurring mixture of gaseous hydrocarbons consisting primarily of methane in addition to various smaller amounts of other higher alkanes. Low levels of trace gases like carbo ...

fields nearby. Speculators had begun searching for oil and natural gas in Jackson beginning in 1920. The initial drilling attempts came up empty. This failure did not stop Ella Render from obtaining a lease from the state's insane asylum to begin a well on its grounds in 1924, where he found natural gas. (Render eventually lost the rights when courts determined that the asylum did not have the right to lease the state's property.) Businessmen jumped on the opportunity and dug wells in the Jackson area. The continued success of these ventures attracted further investment. By 1930, there were 14 derricks in the Jackson skyline.

Mississippi Governor Theodore Bilbo

Theodore Gilmore Bilbo (October 13, 1877 – August 21, 1947) was an American politician who twice served as governor of Mississippi (1916–1920, 1928–1932) and later was elected a U.S. Senator (1935–1947). A lifelong Democrat, he was a fi ...

stated:

This enthusiasm was subdued when the first wells failed to produce oil of a sufficiently high gravity for commercial success. The barrels of oil had considerable amounts of saltwater, which lessened the quality. The governor's prediction was wrong in hindsight, but the oil and natural gas industry did provide an economic boost for the city and state. The effects of the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

were mitigated by the industry's success. At its height in 1934, there were 113 producing wells in the state. The overwhelming majority were closed by 1955.

Due to provisions in the federal Rivers and Harbors Act

Rivers and Harbors Act may refer to one of many pieces of legislation and appropriations passed by the United States Congress since the first such legislation in 1824. At that time Congress appropriated $75,000 to improve navigation on the Ohio and ...

, on October 25, 1930, city leaders met with U.S. Army engineers to ask for federal help to alleviate Jackson flooding. J.J. Halbert, city engineer, proposed a straightening and dredging of the Pearl River

The Pearl River, also known by its Chinese name Zhujiang or Zhu Jiang in Mandarin pinyin or Chu Kiang and formerly often known as the , is an extensive river system in southern China. The name "Pearl River" is also often used as a catch-a ...

below Jackson.

Jackson's Gold Coast

During Mississippi's extendedProhibition

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcoholic ...

period, from the 1920s until the 1960s, illegal drinking and gambling casinos flourished on the east side of the Pearl River, in Flowood along with the original U.S. Route 80 just across from the city of Jackson. Those illegal casinos, bootleg liquor stores, and nightclubs made up the Gold Coast, a strip of mostly black-market

A black market, underground economy, or shadow economy is a clandestine market or series of transactions that has some aspect of illegality or is characterized by noncompliance with an institutional set of rules. If the rule defines the ...

businesses that operated for decades along Flowood Road. Although outside the law, the Gold Coast was a thriving center of nightlife and music, with many local blues musicians appearing regularly in the clubs.

The Gold Coast declined and businesses disappeared after Mississippi's prohibition laws were repealed in 1966, allowing Hinds County, including Jackson, to go "wet". In addition, integration

Integration may refer to:

Biology

*Multisensory integration

*Path integration

* Pre-integration complex, viral genetic material used to insert a viral genome into a host genome

*DNA integration, by means of site-specific recombinase technology, ...

drew off business from establishments that earlier had catered to African Americans, such as the Summers Hotel. When it opened in 1943 on Pearl Street, it was one of two hotels in the city that served black clients. For years its Subway Lounge was a prime performance spot for black musicians playing jazz and blues.

In another major change, in 1990 the state-approved gaming on riverboats. Numerous casinos have been developed on riverboats, mostly in Mississippi Delta

The Mississippi Delta, also known as the Yazoo–Mississippi Delta, or simply the Delta, is the distinctive northwest section of the U.S. state of Mississippi (and portions of Arkansas and Louisiana) that lies between the Mississippi and Yazoo ...

towns such as Tunica Resorts

Tunica Resorts, formerly known as Robinsonville until 2005,

, Greenville, and Vicksburg Vicksburg most commonly refers to:

* Vicksburg, Mississippi, a city in western Mississippi, United States

* The Vicksburg Campaign, an American Civil War campaign

* The Siege of Vicksburg, an American Civil War battle

Vicksburg is also the name of ...

, as well as Biloxi

Biloxi ( ; ) is a city in and one of two county seats of Harrison County, Mississippi, United States (the other being the adjacent city of Gulfport). The 2010 United States Census recorded the population as 44,054 and in 2019 the estimated popu ...

on the Gulf Coast

The Gulf Coast of the United States, also known as the Gulf South, is the coastline along the Southern United States where they meet the Gulf of Mexico. The coastal states that have a shoreline on the Gulf of Mexico are Texas, Louisiana, Mississ ...

. Before the damage and losses due to Hurricane Katrina

Hurricane Katrina was a destructive Category 5 Atlantic hurricane that caused over 1,800 fatalities and $125 billion in damage in late August 2005, especially in the city of New Orleans and the surrounding areas. It was at the time the cost ...

in 2005, the state ranked second nationally in gambling revenues.

World War II and later development

DuringWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, Hawkins Field

Hawkins Field is a baseball stadium in Nashville, Tennessee. It is the home field of the Vanderbilt Commodores college baseball team.

(at that time, also known as the Jackson Army Airbase) the American 21st, 309th, and 310th Bomber Groups that were stationed at the base were re-deployed for combat. Following the German invasion of the Netherlands

The German invasion of the Netherlands ( nl, Duitse aanval op Nederland), otherwise known as the Battle of the Netherlands ( nl, Slag om Nederland), was a military campaign part of Case Yellow (german: Fall Gelb), the Nazi German invasion of t ...

and the Japanese invasion of the Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies campaign of 1941–1942 was the conquest of the Dutch East Indies (present-day Indonesia) by forces from the Empire of Japan in the early days of the Pacific campaign of World War II. Forces from the Allies attempted ...

, between 688 and 800 members of the Dutch Airforce escaped to the UK or Australia for training and, out of necessity, were eventually given permission by the United States to make use of Hawkins Field.

From May 1942 until the end of the war, all Dutch military aircrews trained at the base and went on to serve in either the British or Australian Air Forces.

In 1949, the poet Margaret Walker

Margaret Walker (Margaret Abigail Walker Alexander by marriage; July 7, 1915 – November 30, 1998) was an American poet and writer. She was part of the African-American literary movement in Chicago, known as the Chicago Black Renaissance. H ...

began teaching at Jackson State University

Jackson State University (Jackson State or JSU) is a public historically black research university in Jackson, Mississippi. It is one of the largest HBCUs in the United States and the fourth largest university in Mississippi in terms of studen ...

, a historically black college

Historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) are institutions of higher education in the United States that were established before the Civil Rights Act of 1964 with the intention of primarily serving the African-American community. Mo ...

. She taught there until 1979 and founded the university's Center for African-American Studies. Her poetry collection won a Yale Younger Poets Prize

The Yale Series of Younger Poets is an annual event of Yale University Press aiming to publish the debut collection of a promising American poet. Established in 1918, the Younger Poets Prize is the longest-running annual literary award in the Uni ...

. Her second novel, ''Jubilee

A jubilee is a particular anniversary of an event, usually denoting the 25th, 40th, 50th, 60th, and the 70th anniversary. The term is often now used to denote the celebrations associated with the reign of a monarch after a milestone number of y ...

'' (1966), is considered a major work of African-American literature. She has influenced many younger writers.

Civil rights movement in Jackson

Thecivil rights movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional Racial segregation in the United States, racial segregation, Racial discrimination ...

had been active for decades, particularly mounting legal challenges to Mississippi's constitution and laws that disfranchised black people. Beginning in 1960, Jackson as the state capital became the site for dramatic non-violent protests in a new phase of activism that brought in a wide variety of participants in the performance of mass demonstrations.

In 1960, the U.S. Census Bureau reported Jackson's population as 64.3% white and 35.7% black. At the time, public facilities were segregated and Jim Crow

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws enforcing racial segregation in the Southern United States. Other areas of the United States were affected by formal and informal policies of segregation as well, but many states outside the Sout ...

was in effect. Efforts to desegregate Jackson facilities began when nine Tougaloo College

Tougaloo College is a private historically black college in the Tougaloo area of Jackson, Mississippi. It is affiliated with the United Church of Christ and Christian Church (Disciples of Christ). It was originally established in 1869 by New Yo ...

students tried to read books in the "white only" public library and were arrested. Founded as a historically black college

Historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) are institutions of higher education in the United States that were established before the Civil Rights Act of 1964 with the intention of primarily serving the African-American community. Mo ...

(HBCU) by the American Missionary Association after the Civil War, Tougaloo College

Tougaloo College is a private historically black college in the Tougaloo area of Jackson, Mississippi. It is affiliated with the United Church of Christ and Christian Church (Disciples of Christ). It was originally established in 1869 by New Yo ...

helped organize both black and white students of the region to work together for civil rights. It created partnerships with the neighboring mostly white Millsaps College

Millsaps College is a private liberal arts college in Jackson, Mississippi. It was founded in 1890 and is affiliated with the United Methodist Church.

History

The college was founded in 1889–90 by a Confederate veteran, Major Reuben Webster M ...

to work with student activists. It has been recognized as a site on the "Civil Rights Trail" by the National Park Service

The National Park Service (NPS) is an agency of the United States federal government within the U.S. Department of the Interior that manages all national parks, most national monuments, and other natural, historical, and recreational propertie ...

.

The mass demonstrations of the 1960s were initiated with the arrival of more than 300

The mass demonstrations of the 1960s were initiated with the arrival of more than 300 Freedom Riders

Freedom Riders were civil rights activists who rode interstate buses into the segregated Southern United States in 1961 and subsequent years to challenge the non-enforcement of the United States Supreme Court decisions ''Morgan v. Virginia' ...

on May 24, 1961. They were arrested in Jackson for disturbing the peace

Breach of the peace, or disturbing the peace, is a legal term used in constitutional law in English-speaking countries and in a public order sense in the several jurisdictions of the United Kingdom. It is a form of disorderly conduct.

Public ord ...

after they disembarked from their interstate buses. The interracial teams rode the buses from Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

and sat together to demonstrate against segregation on public transportation, as the Constitution provides for unrestricted public transportation. Although the Freedom Riders had intended New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

as their final destination, Jackson was the farthest that any managed to travel. New participants kept joining the movement, as they intended to fill the jails in Jackson with their protest. The riders had encountered extreme violence along the way, including a bus burning and physical assaults. They attracted national media attention to the struggle for constitutional rights.

After the Freedom Rides, students and activists of the Freedom Movement launched a series of merchant Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

boycott

A boycott is an act of nonviolent, voluntary abstention from a product, person, organization, or country as an expression of protest. It is usually for moral, social, political, or environmental reasons. The purpose of a boycott is to inflict som ...

s, sit-ins and protest marches, from 1961 to 1963. Businesses discriminated against black customers. For instance, at the time, department stores did not hire black salesclerks or allow black customers to use their fitting rooms to try on clothes, or lunch counters for meals while in the store, but they wanted them to shop in their stores.

In Jackson, shortly after midnight on June 12, 1963, Medgar Evers

Medgar Wiley Evers (; July 2, 1925June 12, 1963) was an American civil rights activist and the NAACP's first field secretary in Mississippi, who was murdered by Byron De La Beckwith. Evers, a decorated U.S. Army combat veteran who had served i ...

, civil rights activist and leader of the Mississippi chapter of the NAACP

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is a civil rights organization in the United States, formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E.&nb ...

, was assassinated by Byron De La Beckwith

Byron De La Beckwith Jr. (November 9, 1920 – January 21, 2001) was an American murderer, white supremacist and member of the Ku Klux Klan from Greenwood, Mississippi. He murdered the civil rights leader Medgar Evers on June 12, 1963. Two trial ...

, a white supremacist

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other Race (human classification), races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any Power (social and polit ...

associated with the White Citizens' Council

The Citizens' Councils (commonly referred to as the White Citizens' Councils) were an associated network of white supremacist, segregationist organizations in the United States, concentrated in the South and created as part of a white backlash a ...

. Thousands marched in Evers' funeral procession to protest the killing. Two trials at the time both resulted in hung juries

A hung jury, also called a deadlocked jury, is a judicial jury that cannot agree upon a verdict after extended deliberation and is unable to reach the required unanimity or supermajority. Hung jury usually results in the case being tried again.

...

. A portion of U.S. Highway 49, all of Delta Drive, a library, the central post office for the city, and Jackson–Evers International Airport were named in honor of Medgar Evers. In 1994, prosecutors Ed Peters and Bobby DeLaughter Robert Burt DeLaughter Sr. (born February 28, 1954 in Vicksburg, Mississippi) is a former state prosecutor and then Hinds County Circuit Judge. He prosecuted and secured the conviction in 1994 of Byron De La Beckwith, charged with the murder of th ...

finally obtained a murder conviction in a state trial of De La Beckwith based on new evidence.

During 1963 and 1964, civil rights organizers gathered residents for voter education and voter registration

In electoral systems, voter registration (or enrollment) is the requirement that a person otherwise eligible to vote must register (or enroll) on an electoral roll, which is usually a prerequisite for being entitled or permitted to vote.

The ru ...

. Black people had been essentially disfranchised since 1890. In a pilot project in 1963, activists rapidly registered 80,000 voters across the state, demonstrating the desire of African Americans to vote. In 1964 they created the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party

The Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP), also referred to as the Freedom Democratic Party, was an American political party created in 1964 as a branch of the populist Freedom Democratic organization in the state of Mississippi during the ...

as an alternative to the all-white state Democratic Party, and sent an alternate slate of candidates to the national Democratic Party convention in Atlantic City

Atlantic City, often known by its initials A.C., is a coastal resort city in Atlantic County, New Jersey, United States. The city is known for its casinos, Boardwalk (entertainment district), boardwalk, and beaches. In 2020 United States censu ...

, New Jersey, that year.

Segregation and the disfranchisement of African Americans gradually ended after the Civil Rights Movement gained Congressional passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 () is a landmark civil rights and United States labor law, labor law in the United States that outlaws discrimination based on Race (human categorization), race, Person of color, color, religion, sex, and nationa ...

and Voting Rights Act

The suffrage, Voting Rights Act of 1965 is a landmark piece of Federal government of the United States, federal legislation in the United States that prohibits racial discrimination in voting. It was signed into law by President of the United ...

of 1965. In June 1966, Jackson was the terminus of the James Meredith March, organized by James Meredith

James Howard Meredith (born June 25, 1933) is an American civil rights activist, writer, political adviser, and Air Force veteran who became, in 1962, the first African-American student admitted to the racially segregated University of Mississ ...

, the first African American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

to enroll at the University of Mississippi

The University of Mississippi (byname Ole Miss) is a public research university that is located adjacent to Oxford, Mississippi, and has a medical center in Jackson. It is Mississippi's oldest public university and its largest by enrollment.

...

. The march, which began in Memphis

Memphis most commonly refers to:

* Memphis, Egypt, a former capital of ancient Egypt

* Memphis, Tennessee, a major American city

Memphis may also refer to:

Places United States

* Memphis, Alabama

* Memphis, Florida

* Memphis, Indiana

* Memp ...

, Tennessee, was an attempt to garner support for full implementation of civil rights in practice, following the legislation. It was accompanied by a new drive to register African Americans to vote in Mississippi. In this latter goal, it succeeded in registering between 2,500 and 3,000 black Mississippians to vote. The march ended on June 26 after Meredith, who had been wounded by a sniper's bullet earlier on the march, addressed a large rally of some 15,000 people in Jackson.

In September 1967 a Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and ...

chapter bombed the synagogue of the Beth Israel Congregation in Jackson, and in November bombed the house of its rabbi, Dr. Perry Nussbaum

Beth Israel Congregation ( he, בית ישראל) is a Reform Jewish congregation located at 5315 Old Canton Road in Jackson, Mississippi, United States. Organized in 1860 by Jews of German background, it has always been, and remains, the only ...

. History of Beth Israel, Jackson, Mississippi, Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life website, History Department, Digital Archive, Mississippi, Jackson, Beth Israel. Retrieved August 17, 2008. He and his congregation had supported civil rights. Gradually the old barriers came down. Since that period, both whites and African Americans in the state have had a consistently high rate of voter registration and turnout. Following the decades of the Great Migration, when more than one million black people left the rural South, since the 1930s the state has been majority white in total population. African Americans are a majority in the city of Jackson, although the metropolitan area is majority white. African Americans are also a majority in several cities and counties of the

Mississippi Delta

The Mississippi Delta, also known as the Yazoo–Mississippi Delta, or simply the Delta, is the distinctive northwest section of the U.S. state of Mississippi (and portions of Arkansas and Louisiana) that lies between the Mississippi and Yazoo ...

, which are included in the 2nd congressional district. The other three congressional districts are majority white.

Mid-1960s to present

The first successful cadavericlung

The lungs are the primary organs of the respiratory system in humans and most other animals, including some snails and a small number of fish. In mammals and most other vertebrates, two lungs are located near the backbone on either side of t ...

transplant was performed at the University of Mississippi Medical Center

University of Mississippi Medical Center (UMMC) is the health sciences campus of the University of Mississippi (Ole Miss) and is located in Jackson, Mississippi, United States. UMMC, also referred to as the Medical Center, is the state's only aca ...

in Jackson in June 1963 by Dr. James Hardy. Hardy transplanted the cadaveric lung into a patient suffering from lung cancer. The patient survived for eighteen days before dying of kidney failure

Kidney failure, also known as end-stage kidney disease, is a medical condition in which the kidneys can no longer adequately filter waste products from the blood, functioning at less than 15% of normal levels. Kidney failure is classified as eit ...

.

In 1966 it was estimated that recurring flood damage at Jackson from the Pearl River averaged nearly a million dollars per year. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

, colors =

, anniversaries = 16 June (Organization Day)

, battles =

, battles_label = Wars

, website =

, commander1 = ...

spent $6.8 million on levee

A levee (), dike (American English), dyke (English in the Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth English), embankment, floodbank, or stop bank is a structure that is usually soil, earthen and that often runs parallel (geometry), parallel to ...

s and a new channel in 1966 before the project completion to prevent a flood equal to the December 1961 event plus an additional foot.

Since 1968, Jackson has been the home of Malaco Records

Malaco Records is an American independent record label based in Jackson, Mississippi, United States, that has been the home of various major blues and gospel acts, such as Johnnie Taylor, Bobby Bland, Mel Waiters, Z. Z. Hill, Denise LaSalle, La ...

, one of the leading record companies for gospel

Gospel originally meant the Christian message ("the gospel"), but in the 2nd century it came to be used also for the books in which the message was set out. In this sense a gospel can be defined as a loose-knit, episodic narrative of the words an ...

, blues

Blues is a music genre and musical form which originated in the Deep South of the United States around the 1860s. Blues incorporated spirituals, work songs, field hollers, shouts, chants, and rhymed simple narrative ballads from the Afr ...

, and soul music

Soul music is a popular music genre that originated in the African American community throughout the United States in the late 1950s and early 1960s. It has its roots in African-American gospel music and rhythm and blues. Soul music became po ...

in the United States. In January 1973, Paul Simon

Paul Frederic Simon (born October 13, 1941) is an American musician, singer, songwriter and actor whose career has spanned six decades. He is one of the most acclaimed songwriters in popular music, both as a solo artist and as half of folk roc ...

recorded the songs "Learn How to Fall" and "Take Me to the Mardi Gras", found on the album ''There Goes Rhymin' Simon

''There Goes Rhymin' Simon'' is the third solo studio album by American musician Paul Simon released on May 5, 1973. It contains songs spanning several styles and genres, such as gospel (" Loves Me Like a Rock") and Dixieland (" Take Me to the ...

'', in Jackson at the Malaco Recording Studios. Many well-known Southern artists recorded on the album, including the Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section

The Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section is a group of American session musicians based in the northern Alabama town of Muscle Shoals. One of the most prominent American studio house bands from the 1960s to the 1980s, these musicians, individually or as ...

(David Hood, Jimmy Johnson, Roger Hawkins, Barry Beckett), Carson Whitsett

James Carson Whitsett (May 1, 1945 – May 8, 2007) was an American keyboardist, songwriter, and record producer.

Biography

Carson Whitsett was born in Jackson, Mississippi. He joined his older brother Tim's band, Tim Whitsett & The Imperials ( ...

, the Onward Brass Band

The Onward Brass Band was either of two brass bands active in New Orleans for extended periods of time.

Onward Brass Band (c. 1886–1930)

This incarnation of the Onward Brass Band played often in its early history at picnics, festivals, parade ...

from New Orleans, and others. The label has recorded many leading soul and blues artists, including Bobby Bland

Robert Calvin Bland (born Robert Calvin Brooks; January 27, 1930 – June 23, 2013), known professionally as Bobby "Blue" Bland, was an American blues singer.

Bland developed a sound that mixed gospel with the blues and R&B. He was descr ...

, ZZ Hill

Arzell J. Hill (September 30, 1935 – April 27, 1984),Dahl, Bill. "Z.Z. Hill" Allmusic.com. Retrieved 29 March 2014. known as Z. Z. Hill, was an American blues singer best known for his recordings in the 1970s and early 1980s, including his 19 ...

, Latimore, Shirley Brown

Shirley Brown (born January 6, 1947, West Memphis, Arkansas) is an American R&B singer, best known for her million-selling single " Woman to Woman", which was nominated for a Grammy Award in 1975.

Biography

Brown was born in West Memphis, but ...

, Denise LaSalle

Ora Denise Allen (July 16, 1934 – January 8, 2018), known by the stage name Denise LaSalle, was an American blues, R&B and soul singer, songwriter, and record producer who, since the death of Koko Taylor, had been recognized as the "Queen of ...

, and Tyrone Davis

Tyrone Davis (born Tyrone D. Fettson or Tyrone D. Branch, October 3, 1937 – February 9, 2005) was an American blues and soul singer with a long list of hit records over more than 20 years. Davis had three number 1 hits on the '' Billboard'' ...

.

On May 15, 1970, Jackson police killed two students and wounded twelve at Jackson State College

Jackson State University (Jackson State or JSU) is a public historically black research university in Jackson, Mississippi. It is one of the largest HBCUs in the United States and the fourth largest university in Mississippi in terms of studen ...

after a protest of the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

included students' overturning and burning some cars. These killings occurred eleven days after the National Guard

National Guard is the name used by a wide variety of current and historical uniformed organizations in different countries. The original National Guard was formed during the French Revolution around a cadre of defectors from the French Guards.

Nat ...

killed four students in an anti-war protest at Kent State University

Kent State University (KSU) is a public research university in Kent, Ohio. The university also includes seven regional campuses in Northeast Ohio and additional facilities in the region and internationally. Regional campuses are located in As ...

in Ohio